- Home

- Pauline Fisk

Sabrina Fludde Page 18

Sabrina Fludde Read online

Page 18

‘Are you with the trow?’ he asked. ‘Because if you are, I’ve cooked you these. Cooked them for you special. Caught ’em with my lantern last night. Must’ve known that you were coming. Though I can’t imagine why – there hasn’t been a trow past here for years. Not since I was a boy!’

He held out his hands. In them Abren saw a black pot lined with newspaper, inside of which lay a pile of something white and thin – not chips, as she first thought, but something more like strands of spaghetti.

‘What are they?’ she asked cautiously.

‘They’re elvers,’ the little man said. ‘Baby eels. Their home’s way off in the Sargasso Sea, but they do their growing-up here in the river. Unless the fisherman gets them first, of course! Like I did last night. Here you are.’

He thrust his gift at Abren, who found herself clutching not a pot, after all, but a bowler hat turned upside-down!

‘They’re a real tasty treat,’ the little man said.

‘I’m sure they are,’ Abren replied, trying not to shiver at the thought of eating baby eels whose struggle to grow up had ended in an old man’s hat. ‘You must come and share them with us.’

The little man didn’t say no. Perhaps he’d caught a whiff of coltsfoot coming from the trow. He followed Abren back to it, and he and Sir Henry greeted each other like long-lost brothers – fellow claypipe men sharing the secret pleasures of a good smoke.

The elvers were delicious, too – far better than the one-pot stew. Everybody ate them, even Abren, for all her qualms. Maybe it was the fresh air that did it, or the fact that she hadn’t eaten much over the last few days, but she was starving hungry. After she’d finished all the leftovers, the little man removed the newspaper from inside his bowler hat, wiped it clean and gave it to Sir Henry. It had been his father’s hat, he said. All the old trow masters wore them. It had been the badge of their trade.

Sir Henry took the bowler hat as if it were made of gold. He put it on his head at the little man’s insistence, and for all his claiming that he wasn’t worthy, he wouldn’t take it off again. It was getting late by now, but with his new hat on his head and his pipe in his mouth he plainly didn’t want to go to bed.

Neither did the rest of them. It was getting cold as well as late, but none of them wanted to shut themselves away, fore and aft, in their cabins. Pen invited the little man to tell them about his boyhood days when trows still sailed the river. The little man started talking, and the river rocked them. Abren found herself drifting into a strange, contented half-sleep – only to come to herself again with everybody looking at her.

‘What is it?’ she said.

‘Our friend here’s wondering about the flood. He’s never seen the likes of it in all his days. I said that you could tell him all about it.’

It was Phaze II who spoke for all of them. Phaze II giving Abren the chance to explain herself at last! Abren looked round at them – Pen curled against Sir Henry, Bentley absent-mindedly nursing his saxophone, Phaze II staring at her as if he’d known all along that she had a story to tell, but he’d never asked. Never pushed it. Not until now.

And now was the right time! Abren could tell. She ran her finger down the frayed edge of her comfort blanket. Even the little man was watching her as if there were things that he, a stranger, wanted to know. This was her chance to tell them all about herself. To tell it all.

And so she did.

Under angels’ wings

In the early hours the little man went home, disappearing into the darkness as he had come, humming his tune and puffing on his pipe. When they awoke next day, his house stood quiet against the river bank without a sign of life.

It was a windless morning and they cast off at first light, with a long day ahead of them according to Sir Henry. The river was still high, and as smooth as glass, and they flowed silently down it with a sense of wonder. It was as if Abren’s story had touched them all. Bentley played his saxophone, and Abren sat in the bow looking straight ahead. She’d thought that she might turn to dust when she’d told them everything she had to say – but here she still was.

Bentley gave up playing and came and sat beside her, not a word between them but for just this one day she was his ‘cousin from away, come to stay’. That night they moored under Wainlode Cliff. It would be just as long a day tomorrow, sailing into the estuary, so they bunked down early. The sky was clear, the moon as full as a moon could be and the river swelling under the trow. They had reached the tidal passage of the river, and Abren could feel it turning under her as she fell asleep.

Next morning she was woken by a sprightly breeze which knocked the ropes and shook the leaves in the trees. The Princess of Pengwern bobbed on the river, as if impatient to get away. Everything felt different. They left the tall pink rocks of Wainlode, drawn by the current and driven by the breeze. On one side of the river a row of willow sticks had been pushed in to mark the edge of a sandbank. They steered around it, travelling out into deep waters where the cross-currents were tricky and all hands were required to work the sail and man the sweeps.

Later, standing at the tiller with Sir Henry, Abren asked about the sea. She had been looking for a first glimpse of it around every bend in the river, but hadn’t even caught a whiff of salt. Sir Henry said that it wasn’t far now – but first they had to get through Gloucester.

Abren hadn’t known that Gloucester existed, let alone lay ahead between her and the sea. But no sooner had Sir Henry told her about its significance in the river’s history than she saw it up ahead, and felt it drawing them out of the river’s quiet havens into public view. Chimneys, spires and roofs appeared, roads and pavements and towing paths where curious passers-by stopped to stare. Abren saw offices and factories, apartment blocks and houses, caught a glimpse of warehouses, saw a busy road bridge up ahead and a lock beyond it, with massive wooden gates. Here a crowd stood watching the Princess of Pengwern making her way downriver.

Abren couldn’t wait to carry on past the lock, saying goodbye to Gloucester as quickly as possible. But Sir Henry shouted for the sail to come down, the anchor to be dragged, and the Princess of Pengwern poled round so that he could steer her out of the fast-flowing centre of the river, towards the lock gates. A bell rang in the lock-keeper’s cabin, and the traffic stopped to let the road bridge rise and let them through.

‘What’s going on? Why aren’t we carrying on down-river? Where are we going?’ Abren asked.

Sir Henry didn’t answer. His bowler hat in place, he steered the Princess of Pengwern into the arms of the lock. Its massive wooden gates, built to withstand tons of water, crashed shut behind them, cutting them adrift from their journey. Abren felt as if the lock’s concrete walls, stretching high above her, were a prison cell – and the lock-keeper her gaoler.

‘What are we doing?’ she cried out.

Nobody heard her. They were too busy watching the water level rising and the Princess of Pengwern moving up and up until they could suddenly see where they were going – into a dock with pleasure cruisers berthed in rows, and warehouses converted into shops. The water in the lock filled up to the top, and the Princess of Pengwern prepared to inch out into the dock. A little tug came and helped her, leading her across the harbour basin to berth beside a tall sea schooner. Washing hung from the schooner’s rigging, and the tang of the sea wafting off it was unmistakable.

The sea at long last! Abren strained to catch a glimpse of it down the dock, as if its breaking waves lay somewhere just beyond the schooner.

‘We’ll stop for lunch,’ Sir Henry told them all. ‘Stock up on provisions and stretch our legs. Then meet back here at two o’clock, and make our way down the canal. If we’re lucky, we’ll get a sunset sail on the Severn Sea. But if not, we’ll moor the night at Sharpness ready for the morning.’

The others were excited – but Abren only heard the one word.

‘Canal?’ she gasped. ‘But what about the river?’

‘The river’s treacherous between here an

d the sea,’ explained Sir Henry. ‘Full of rip tides and quicksands. Only the most experienced master mariners would have sailed down it in the old days, even when the trows were manned by crews who knew the river like the back of their hands. And that excludes us, I think we’d all agree!’

He looked round at them, everybody grinning as if they did, indeed, agree. We’ve done the best we can, the general opinion seemed to be. And it’s been a wonderful experience! And we’d like to make it to the sea, so let’s go by canal. Given what you say about the river, it makes good sense.

It might have made good sense to everybody else, but not to Abren! She turned away. To her it seemed like giving up. Bentley spoke for the rest of them, thanking Sir Henry for their great adventure. But he didn’t speak for Abren.

She disembarked at the first opportunity, making off down the wharf as soon as their backs were turned. She didn’t know where she was going, and didn’t really care. What she wanted was time alone, to think. She wandered past old customs buildings, corn merchants and flour mills which now were turned into restaurants, hotels and shops. At the end of the first dock she found a second one, and between the two of them she came across a church with a bell hanging over it and an open door.

‘The Mariners’ Church,’ said the notice nailed to the door, ‘welcomes travellers.’

Abren slipped inside, wondering what sort of welcome she could expect. Inside she found a simple, bright room which was cosy but worn, its smell of polished wood reminding her of the cabins on the Princess of Pengwern. She sat down on a pew with a bursting cushion, and lost herself in questions about her journey and why it had suddenly gone all wrong.

Over her hung a tapestry commemorating centuries of men, women and children who had lived and worked upon deep waters. Abren stared idly at its woven sunshine and gulls, boats and fish, flowers and stars, sunrise and sunset. They reminded her of her little comfort blanket, and she absent-mindedly fingered its frayed edge. At the bottom of the tapestry was a row of figures woven in every imaginable size, shape, costume and colour, all holding hands and dancing over waves which looked like wild white horses.

Abren looked at them, and remembered the picture in the library book – the one of the girl who had reminded her of herself. Now she saw herself again in these dancing figures. Saw the child who’d arrived in Pengwern not knowing who she was. The one who’d lived with Bentley and been his cousin from away. The one who’d hidden in the limbo-land beneath the railway bridge. Who’d found out all about her past by reading a poem picked up off the floor.

She saw the child who always blamed herself, even when things weren’t her fault. And she saw the child who’d made it through. Made it without cutlasses and amber tea and mountain bees. Made it despite everything.

Abren left the church, knowing that her journey hadn’t gone wrong. She’d reached its end, that was all. The end of the story, with all the jigsaw pieces put together, and the start of a new one. Without a backward glance, she hurried between the docks, knowing exactly what she was going to do.

Back at the Princess of Pengwern, nobody was about. Abren took off her little blanket and left it with a note, saying that where she was going she no longer needed charts. Then she untied the coracle from the stern of the trow, hauled it over her back in just the way Sir Henry had done on the town walls, and waddled off like a turtle.

At the end of the wharf, she slipped through a passage between the lock and the main road, found a footbridge beyond it and slid down to the river. Here she dropped the coracle into the water, holding on to the towing rope and prepared to jump in, steadied by the paddle.

‘Where d’you think you’re off to this time, then?’ a voice said.

Abren looked up the bank, and there was Phaze II. He stood with his arms folded over his chest, his expression suggesting that Bentley might forgive her for walking out on him last Christmas – and now doing it again – but he had had enough!

‘It’s not that I want to walk out on you,’ Abren said, blushing at being caught. ‘It’s just that I’ve got to go. There’s a new adventure waiting for me up ahead!’

‘Perhaps you’re not the only one who’s waiting for a new adventure,’ Phaze II said.

‘Perhaps I’m not. But this one’s mine. I’ve got to make it on my own. And it’s going to be dangerous! You heard Sir Henry,’ Abren said.

‘You heard him too!’

‘I know I did. But I’ve still got to go.’

Phaze II glared at Abren. She thought of all the things she didn’t know about him, starting with his real name, and ending here with his wanting to come too.

‘You can’t just leave me. You don’t understand. Our stories belong together,’ he said.

‘I’d let you come if I only could. Believe me, I would.’ Abren jumped into the coracle.

Feeling guilty and wretched, she pushed it out from the bank and left Phaze II behind. He stood and watched as she clutched the paddle, trying to remember what Sir Henry had taught her. She turned her eyes away from him and fixed them straight ahead. If she looked back, she would go back. And then she’d never make this all-important journey which was hers alone. Never dance the dance or find the new adventure.

Abren paddled on determinedly. The tide was at its highest, on the turn and ready to help her on her way. It got hold of the little coracle and whisked it down-river with no chance of turning back and very little need for paddling skills. Abren smelt the sea again – not a distant whiff, but full and strong and waiting for her up ahead.

She lifted her head and smiled a smile like Pen’s – there for all the world to read and impossible to shift! The world viewed from the river was a wondrous place, full of life and colour, ever changing, ever bright. She saw a reedy sandbank where herons dipped, and a spring-green woodland where walkers threw sticks to their dogs. Saw meadows full of cattle and swaying wild flowers, and the sky stretched over everything like an enamelled jewel.

Only when Abren reached a graveyard of old trows did a shadow fall over the journey. At first she couldn’t make out what those shapes were, half-rotting among the brambles, disfiguring the bank. But then she saw the stark remains of a massive hull, and realised that this was what the Princess of Pengwern must have been like before Sir Henry rescued her.

The coracle carried her away from it – but the shadow remained. Abren passed a lonely flatland without a soul in sight. Saw a train against a bare cliff. Saw a church without a village, and a power station built upon an empty shore, on the edge of a silent lagoon where nothing stirred and nothing grew.

The river was widening all the time, twisting and growing, and the shores were disappearing like distant lands. Abren drifted on, feeling strangely gloomy and unsettled, despite the smile still stuck across her face. The afternoon was closing in, the sun was lowering in the sky and the coracle felt heavy and tired. For some reason, it seemed to drag rather than dash. The sea felt close – but the coracle seemed to hang back.

Abren gripped the paddle doggedly and twisted it through the water. A lock came into view – a great black thing protruding into the river and blocking her view. She imagined Sir Henry’s canal beyond it, and looked in hope for the mast of the Princess of Pengwern. But for all that she longed to see her friends again, she found the lock empty as she drew level with it.

She carried on, strangely disappointed for a girl who’d wanted to make this journey on her own. The tidal current took her round the end of the lock – and she found herself facing the Severn Sea. The land fell away and the estuary opened out, as pale and silky as a huge pearl. In the distance Abren could see a bridge stretched over it. The last bridge on the river – and soon she would have left it behind! Abren looked at its copper cables, shining mint green in the evening sun. The bridge seemed to stretch for ever, with no visible starting point or destination.

Suddenly she began to cry. Maybe there were cars upon that bridge, travelling on for ever, and people too. But it looked so empty from down here on the ri

ver. Not a soul in sight not even another boat. Abren drifted towards the bridge and the white-topped waves all around her ran lonely lives against the setting sun.

Abren rocked and bobbed and drifted on, feeling lonely too. The bridge drew close. Beyond it was the Severn Sea, and behind her was the river. She had nearly made it, at last! Nearly done what she’d set out to do! She turned to take a final look back upriver towards Plynlimon.

Here I am, she thought, as if the mountain man could see her even here. I made the journey, and you didn’t stop me!

It should have been her final triumph, but the moment just felt empty, with no one to share it. In the distance, Abren could have sworn she heard the mountain man having the last laugh, as if he could have told her that even if she won there’d be a price to pay. A price for everything!

Abren raised her fist at him, clenched as if to say that no matter what – alone or not – he could never keep her down. And, suddenly, as if the last laugh were hers after all, she saw something in the water. It bobbed behind the coracle, travelling in its wake, caught up in its long towing rope.

It couldn’t be – and yet, unbelievably, it was …

Phaze II.

How he had done it – jumped in after Abren and survived a towing-rope ride along this wild stretch of river – Abren would never know. And neither, in the long years yet to come, would Phaze II ever be able to explain it. But that was what he’d done.

Abren let out a cry. She hauled him in, just about avoiding capsizing the coracle in her hurry to get him on board, punch the life back into him and wrap him in a great wet bear-hug.

Phaze II. Her friend. What, how, why …?

‘Yours isn’t the only river flowing out of Plynlimon,’ Phaze II said. ‘And it isn’t the only river in this estuary. There are other rivers too, and other stories to be told. And mine is one of them.’

Mad Dog Moonlight

Mad Dog Moonlight The Red Judge

The Red Judge Midnight Blue

Midnight Blue Sabrina Fludde

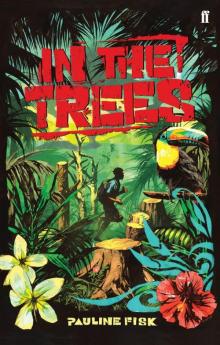

Sabrina Fludde In the Trees

In the Trees