- Home

- Pauline Fisk

Midnight Blue Page 4

Midnight Blue Read online

Page 4

Arabella pushed her way through the darkness of the scullery with its smells of mouse and freshly chopped logs, past the old stone sink in the corner by the window and out into the sunshine. Jake bounded up to her and wove his silky body between her legs. Arabella crossed the terrace and slipped through the gate into the orchard. She half skipped, half ran between the apple trees and long grass, scattering bees and sheep and smelling the grass and pollen and earth. Every now and then she stopped to put down the basket and rest her arms. She heard the steady mumblings of the harvester on the hill above.

'Come on Jake! That's a good boy! I'll beat you there.'

She climbed over the stile into the garden meadow and began to run again, up towards the holly grove. She could see the harvester on the field above it, moving up and down. She could hear the shouts of men. Jake ran ahead of her. He plunged into the dark shade of the holly grove. She hesitated before following him, putting down her basket to rest again, aware that if there was any other way up to the top, she would have taken it.

The holly grove was ancient. The trees were twisted and dark, their branches tortuous. They formed a dense, gnarled ring, with a large mossy clearing in the centre. You slipped into that ring and it was as if you'd entered another world. Arabella looked towards it now. Long strands of fleece hung like listless washing on a line. Last dots of pink foxglove wilted in their shade.

She started pushing her way between the trees. Nothing else moved. Not a branch or bird, an insect or the smallest leaf. Quickly finding herself caught up in branches, Arabella was forced to stop and put down her basket. The buzzing world seemed to stop like her and hold its breath. Up above her, near the top, she could hear Dad’s harvester. It seemed a million miles away. She could have stood here, caught up, for the rest of the day.

'What's the matter with me?' Arabella’s words fell like pebbles into a pond. They rippled and then everything was still again. 'Whatever's the matter?' she said again and despite the day's heat she found herself shivering. 'Come on Arabella, let's get on. They must be starving up there. And thirsty too.'

She picked up the basket. 'I'm talking to myself again,’ she said. 'Talking out loud. Mum says I mustn't do it, but she does it too.'

Dad was down off the harvester, cursing at it because something had gone wrong and it always happened when you most wanted it. Mr Onions was trying to help him work out what to do, and Ned and Henry were trailing across the field, delighted with the chance to stop work.

Mrs Onions appeared over the top of the hill with her husband's lunch. She like the rest of them lived beyond Roundhill, down in the cottages at the back. A small cat followed her. It rushed away in fear when Jake came bounding up.

‘Jake, you rogue,' Mrs Onions said. 'Look what you've gone and done.' She pulled his ears playfully and ran her hand down his back. 'Where's that girl of yours?' she said. Jake pulled away from her as if he didn't have time to waste. 'I beg your pardon, Jake,’ she said. ‘Is something wrong with you?'

Dad lifted his head out of the engine. ‘Is something wrong with who?' he began. But before Mrs Onions could answer, he saw something beyond her heading their way - Arabella running up the field towards them all.

'Dad! Oh, Dad! Help!' she called.

They all started running towards her. Jake bounded ahead. He leapt and wove his way through the harvest, Dad fast on his heels. Arabella fell into Dad’s arms, shiny with sweat, completely out of breath. ‘Dad! Oh, Dad! You’ve got to help!’ she said. Dad got hold of her. She tore herself free.

‘You’ve got to come,’ she said.

‘What is it?’ he said.

‘A girl,’ she said. ‘Down in the holly grove. She’s just lying there. She looks dead.’

7

Bonnie drifted in and out of sleep, and the clock ticked and it comforted her. Gradually she became aware that she lay in a large bed, that her head was supported by a soft pillow smelling of roses, that light, crisp sheets rustled around her as she moved. Through a haze she heard voices, but her eyes were too heavy to open and she couldn't see who spoke.

'Poor little lovely,’ said the first voice.

‘Will she be all right?' said the second.

‘I’m sure she will, but I’m glad you found her.’

‘Yes, but what’s wrong with her?’

One of the voices, weirdly, was Maybelle's. 'I don't know what's wrong,’ it said. ‘I’m fairly sure there are no broken bones. She appears to be sleeping, so that must be what she needs. I think the best thing we can do is keep an eye on her to make sure she’s all right.’

Bonnie fell asleep again. She felt safe, comfortable now. The clock ticked. It was the clock in Maybelle's bedroom. She felt the golden glow of sunshine on her face. But what had happened? As her mind drifted away, Bonnie saw a huge balloon falling through the sky, a world rushing to greet her, ropes, a swinging gondola, a boy's face leaning over her...

She woke again, briefly. The sun had moved round. The tick of the clock was louder and closer. She struggled to open her eyes and stared at the tulip motifs carved upon the base of the bed. They meant she wasn't home after all, for this wasn't Maybelle's bed. She'd never seen this bed before. Where was she?

'I've got to go and get Mr Onions' tea now. Is there anything I can do for you before I go?'

Bonnie struggled to find the person behind the new voice but her eyes wouldn’t stay open. She began to drift away again and dimly heard Maybelle again.

'Don't worry, Mrs Onions. Everything’s all right. I've got a spare hour so I’m going to sit with her. Everything’s in hand downstairs.'

When Bonnie woke again, the clock was striking the hour. She opened her eyes. The room was dark, the day long over. She lay still, gradually taking things in. She'd never been inside a room like this before. The ceiling sloped above her, criss-crossed with black, craggy wooden beams. It sagged and the walls bulged, plaster crumbling off them revealing bits of ancient stone. Beyond the bed, an old black hearth reminded her of the row of antique shops in the road behind Grandbag's flat. There were china dogs upon the mantelpiece and books on shelves.

Suddenly, over by the open window, a seated figure moved. Bonnie started. It had been so quiet and still she'd not known anyone was there. Her bedcovers rustled, but the figure didn't seem to notice. It looked up at the sky. There was something about it.

Then the head moved slightly, tilted to the side. Bonnie recognized the gesture. She stared through the moonlight of this unknown room. It was Maybelle's way of tilting her head, Maybelle's way of resting her shoulders, Maybelle's chin now on Maybelle's hand.

What was Maybelle doing here?

'Hello, Mum. Is she all right?'

Bonnie's skin went cold all over. Why could she hear her own voice when she wasn't speaking? The figure at the window turned. It was Maybelle's face too, but she wore a cotton, tightly-buttoned, rosy nightdress which Maybelle never would have worn, and her face was tired.

'Yes. She's all right. She's only sleeping. She'll be fine again by morning. Have you fed those cats yet, Arabella?'

'Not yet. I'll do it now. I can't help imagining - I mean, you look at someone and they’re a stranger, but I can’t help imaging that we might become friends. Does that sound silly? I mean, I don’t even know her.'

Bonnie's heart thumped so loudly she couldn't believe they didn't hear it. She moved her head slightly, anxious that neither of them should know she was awake. Who was it who spoke with her own voice? Through slits of eyes she stared towards the doorway. A girl stood there, shining in the moonlight. Bonnie bit her lip so as not to cry. She was staring straight at herself.

Up in the holly grove, it was dark now. Sheep rustled among the dusty roots. Up above the circle of spiky branches, a first star shone with a light that seemed to call from other worlds.

The shadowboy slithered under and between the holly branches and out onto the hillside. Night animals carried on their business all around him. Owls swooped over the roofs of the farm

buildings below him. Bats chattered in the evening air. Mice ran along hedgerows. A thin, light-footed cat stalked its prey.

The boy began to pick his way down the meadow. The navy sky was filling with glassy bits of stars. He came down at the back of the house. This was where they'd brought the girl. To one side of the house was a fenced orchard with a little stile and sheep paths that snaked up from it onto the hill. To the other was a farm gate and a yard and the barns. He crept down to the gate. The grass beneath his feet hardly rustled as he walked over it. The birds and animals around him moved about as if nobody else was there. He swung his thin, pale body over the top bar, prepared to slink across the yard, but a side door opened, throwing out a patch of yellow light, and a figure appeared.

'Come on... come on... come on…'

It was a young girl with yellowy-blond hair. Her hands were full of dishes of food and she rattled them together and called again.

From out of the barns and the long grass of the meadow and under the gate as if he weren't there, from along the terrace and over the yard and from the orchard on the side of the house the farm cats appeared. The girl put down her bowls and disappeared. She returned again with a jug of milk. The cats meowed and lapped and rubbed themselves against her legs and lapped again and she laughed at them all.

'Arabella, get a move on. You ought to be in bed.'

'All right, Dad.'

Out on the yard, the boy heard the door rattling shut. The cats continued to lap. The boy looked right across the valley at the little dots of other farmhouses that brightened all the time, as the darkness grew. He slithered across the yard so quietly that not a cat turned to see who was there, not a cat noticed as he slid the latch and slipped into the barn.

There was fresh grain waiting for the merchant to come for it, and bales of straw and new-mown hay. The thick, musty smell nearly overwhelmed him but the shadowboy had a job to do. He tiptoed forward. He heard rats scampering in corners. His hands felt their way along the straw until he felt something that did not prickle, that did not crack beneath his touch, something soft as a woman's dress, handfuls of the stuff.

The shadowboy held it up before his face. In the darkness it seemed as black as night. It was the balloon, laid out upon the straw where they had put it when they'd brought it down from the hill. His hands crept over it carefully, felt the fine, strong weave. When he was satisfied that it wasn't torn, he felt and checked the ropes. Then he reached beyond the ropes and found the wicker gondola. Everything was there.

Suddenly there was a din outside. The shadowboy crept to the door. Something dark was running across the yard. He peered between the cracks in the barn door. Agitated owls swooped and shrieked and fluttered. Squawks of distress came from the henhouse. The side door was flung open and a man appeared. The boy heard a shot ring out. He saw the fox, with a broken, mutilated chicken in its mouth, escaping.

The man swore at his failure to hit it. ‘Damn and blast,’ he said, then he went back in and slammed the door.

The shadowboy slithered out into the yard again. He'd done what he came to do. With the gun's explosion ringing through his head, he began to follow the fox's trail back up the hill. He followed it up the sheep's path, back through the holly grove and over the half-harvested top meadow. He followed it over the stone wall and among the bracken and whinberries and wild rambling heather of the top. Then the path divided. One way led to the white stones on the very top. The other led to a lower, softer bulge of a hill.

The fox climbed this lower hill and the boy followed him down the other side. The fox knew its path well. In the darkness the shadowboy saw a cluster of cottages tucked in beneath the brow of the hill. He crept towards them. They were bleak, brave little places ringed with rowan trees, hawthorn hedges and crumbling stone walls. Smoke drifted to greet him. Yellow dots of lights shone out of windows.

An old man sat out in the porch of the first cottage, cleaning his garden tools. A woman appeared round the side of the cottage, from her own henhouse. ‘Have you shut ‘em in?’ the old man said. ‘Fox is out. I seen him running by.’

‘Course I have. I wouldn’t let him get ‘em,’ she replied.

It was a grand night. She stopped and said as much, looking up at the sky. ‘I wonder how the little girl’s doing,’ she said. ‘I wish they’d brought her back here. I’d like a little girl to nurse.’

The old man laughed. ‘Silly woman. You’ve got me to nurse.’

‘You, Onions, you?’

'And the cats and the hens and the sick hare and the hedgehogs and that silly fat sheep of yours.'

Laughing, they both turned into the house. 'I'll get us a bite of supper,' the old woman said, to which the old man replied, 'That'll be nice. Harvesting makes me awful hungry. Do you know, I think it's turning chilly.'

They shut the door. The shadowboy wondered what it must be like to be a person, to need to eat to stay alive. He wondered what it was like to feel cold, to want to close yourself indoors away from the great, wide, open sky. It was different for him. He never felt cold. He never felt tired. He didn't have a lifespan. He simply did what he had to do.

8

It was light when Bonnie woke again. The chair by the window was empty. She was alone. She sat up. A dressing-gown had been thrown across the counterpane, and she plucked at it and wrapped it round herself. She got out of bed and began to explore, first the half-opened wardrobe with clothes peeking out of it, then the mantelpiece with its plants and ornaments. Her little cardboard suitcase leaned against the dressing-table. She turned to pick it up, and then she saw, on the dressing-table top, a silver frame with a photograph of Maybelle and herself in it.

'I don't understand.'

Bonnie said the words out loud and a cream cat jumped off the bedside chair and ran away. She leaned across the dressing-table and picked up the photo, staring from it to herself reflected in the mirror and then back again. The clothes were different, and the hair. But the likeness was enough to make her shiver.

'I don't understand.'

Bonnie remembered the woman in the chair and the moonlit girl in the doorway. She turned her head and there was Maybelle's clock, Maybelle's own bedroom clock, ticking its way towards the chiming of another hour. She shivered again and dropped the photograph back quickly where she had found it, and crept away from it towards the door. Where was she, and what was going on here? She opened the door and half expected to find the hall to Maybelle's flat on the other side of it, to hear the radio's murmur in the kitchen, Maybelle crying in the bath, Grandbag shouting crossly from the bedroom that she wanted her early morning cup of tea.

But it was a strange world on the other side of the door, a dark, heavy-timbered, stooping, sagging corridor with doors off on either side, the sort of place you only ever read about in books.

'I feel like I'm Alice,' Bonnie whispered to herself. 'I haven't gone down the rabbit hole but I'm surely dreaming all the same.’

She began to creep down the corridor, pausing carefully at each doorway in case boards squeaked. She came to the staircase. The walls were full of portraits that bore her likeness.

'I am Alice,' she thought. 'This is Wonderland! Who are these people…?' She turned nervously away from the paintings and followed the corridor to its end. In the dark she saw a flight of narrower, more tortuous stairs. 'I wonder what's up there?' she said. She began to climb and, as she did so, she remembered another flight of stairs, another day, the flint-faced house, the room with the glass dome at the top.

Bonnie’s progress was halted by a hatch. She pushed and it slid open. With ease she climbed, not into a light and airy room but into the stuffy darkness of a long, low attic full of packing cases and tea chests, old books, bits of furniture and rolled-up carpets.

At the far end sunlight filtered through a sloping roof-light. Bonnie padded towards the light, just able to stand straight beneath the ridge beam. The floor was uneven and in places it was broken. She stooped down and looked through one hole into th

e bedroom where she'd slept. Then she looked through another hole. She could see coat-hangers and clothes and a wardrobe door that was half open and a corner of a bed beyond, with a sleeping girl in it.

Getting up again, Bonnie peered out of the window. The roof sloped down and there was a flat bit with a wall around it and she thought, 'Let’s get out there and take a look around. Get an idea of where I am.'

She pushed open the window, showering her face and hair with dust. Then she slid out onto the roof, slithered down onto the flat bit and leaned over the wall. A fresh breeze gently stirred her hair. She looked up into the sky. It was streaked with orange sunrise stripes and the clouds were pink. She looked down. The valley was pale with morning mist. She'd never seen such an empty landscape. No houses, no cars, no kids on bikes, no shops or buses.

Suddenly the ground seemed to come up at Bonnie. She thought, 'It's a long way down there,' and felt giddy. She turned back towards the sky-light and began to scramble in again. The attic was warming up for the day. The air was still. She felt as if she couldn't breathe properly, began to pick her way back carefully between the holes in the floor…

And then she saw something. What was it? An open box on the top of a tea chest contained a coil of wooden beads. Bonnie had seen them before. She was sure she had. She picked them up - and then she saw the bits of telescope beneath.

'Hello.'

A face poked through the hatch.

'Michael,' she said.

'Yes?' A body climbed up into the attic. It was Michael. He looked at her with grey, still eyes.

'What… what are you doing here?' Bonnie said.

He smiled. 'That's just what I was going to ask you,' he said. 'There's really nothing to see up here. Do you want to come down and get some breakfast?'

Mad Dog Moonlight

Mad Dog Moonlight The Red Judge

The Red Judge Midnight Blue

Midnight Blue Sabrina Fludde

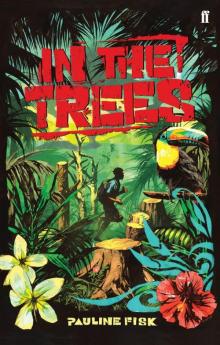

Sabrina Fludde In the Trees

In the Trees