- Home

- Pauline Fisk

Sabrina Fludde Page 4

Sabrina Fludde Read online

Page 4

Far from giving up, Fee doubled his busking efforts. Night after night, rain or clear, he was out there on the hill. It was a busy time for all of them. Mena doubled her efforts too, her tailor’s dummy up to its neck in office-party frocks. Even Bentley found himself caught up in Christmas preparations, staying late for rehearsals of the school pantomime, in which he was lumbered with the role of Chief Executive of Santa’s Toyland.com

He pleaded with Abren to come and see it – and she said that she would. But on the night she cried off. She was feeling sick, she said. And maybe the thought of leaving her fortress did really make her feel sick, but the more important truth was that she had some Christmas preparations of her own, and wanted to get on with them.

So, when they’d all gone out, Abren settled down to make a Christmas present for Bentley, Fee and Mena, stealing a corner of party-frock cloth and a couple of skeins of embroidery silk, and starting to stitch a picture of birds and flowers, copied from her comfort blanket. When Fee and Mena came in, teasing Bentley over his success, Abren hid away her handiwork.

From then on, however, every time she was alone she did some more – stitching as fast as she could because Christmas was drawing close. And with its bustle of excitement came unexpected fears. What would Christmas Day bring for Abren Bytheway, playing the part of an ordinary girl in an ordinary family? What memories and questions would it trigger?

Abren felt the tension building up – not just in her, but in Mena too.

When Fee brought in a tree for them to decorate, Mena said that the real star of Christmas wasn’t made of tinsel, it was made of openness and trust. She looked at Abren as she said it, and Abren blushed. Then, the next day, Christmas Eve, busy cooking everybody’s favourites while Fee was out dressed up as Santa Claus on Pride Hill, she suddenly said, ‘I wonder what your mother’s doing right now. I wonder if she’s missing you.’

Again she looked at Abren, as if blaming her for something. Abren flushed. She didn’t say a thing, but when Mena turned to get something out of the oven, she slipped from the room, stumbling down the stairs with tears pricking her eyes. If it hadn’t been for bumping into Bentley, on his way to market for their last-minute shopping, she didn’t know what she would have done.

‘Do you want to come?’ he said, as if he could tell that something was wrong.

In the end, Abren was glad that she said yes. Down in the market – surrounded by a sea of turkeys, geese, wild hares, pheasants, partridges, huge slabs of pork and rolls of beef – it was impossible to think of anything but Christmas. Bentley dragged her between stalls of fruit, vegetables, nuts, home-made pork pies, home-cured bacon, jars of fat olives, slabs of pinky salmon, floury loaves of bread and twists of rolls, new-laid free-range ducks’ and hens’ and quails’ eggs, and every sort of cheese that Abren could have imagined, from plain to holey and from starkest white to pinks and greens and oranges.

He did the shopping, and Abren helped carry the bags, trying to keep up with him. The market hall was heaving, everyone pushing and shoving, and in the crowd they became separated. Abren found herself wandering on her own down an avenue of flower stalls. At the end she saw a boy who she thought was Bentley. But when he started coughing, she realised that he was someone else.

She fixed her eyes on him – a tall, thin boy with a big black coat, looking at her as if they’d met before. And he looked familiar to Abren too. But only later did she realise that he was the boy she’d seen going through the bins. The one who’d left the roses behind, but no food.

She turned away, bumped into the real Bentley and followed him home. Here Mena said that she was sorry for her quick tongue, and gave Abren a hug. Abren said it didn’t matter, but she lay awake that night, thinking about her mother. What was she doing now? Was she missing Abren? Was she out there somewhere, dressed as Santa and filling Abren’s stocking just in case she came home? Was she looking for her – looking even now, in the middle of the night?

Abren closed her eyes and tried to sleep. But her questions wouldn’t leave her alone, and finally she got up and went downstairs. In the kitchen everything was ready for the morning, a testimony to Mena’s hard work. The turkey waited for its chestnut-and-pork stuffing. The Christmas pudding sat with a cloth tied over it. The Brussels sprouts had been peeled and left to soak in a pan. And even a glass of sherry had been left on the table, with a box of chocolates bearing a note to ‘[email protected] – from your Chief Executive!!’

Abren opened up the luscious chocolates which the note said were ‘for all the busy elves who work so hard to wrap up Santa’s presents’. The other elves weren’t around to share them, and suddenly Abren couldn’t resist making a start. And once started, there was no stopping! Champagne truffles. Chocolate fudge. Hazelnut pralines. Cherry kirsch. Butternut delights. Mocha marzipan. Whisky cream. Orange fizzes.

Abren ate until her stomach heaved. Until the box was empty and she felt too sick to think about her mother or anything else. Then she went to bed, knowing that the chocolates had done the trick. No questions asked was still the order of the day!

Bentley’s carol

Abren came downstairs on Christmas morning to find everybody teasing everybody else about the chocolates. As soon as she appeared, they turned on her with the empty box. It had to be her, they said. She was the chocoholic in the family – the one who’d licked her pudding plate clean on that first day, and had been at the chocolate ever since!

‘I’m not the one who spends his dinner money on chocolate bars!’ Abren teased back. ‘And I’m not the one who keeps a secret store in her sewing-machine drawer!’

Everybody laughed. Abren changed the subject by showing them all the contents of her stocking, and Bentley showed his too, marvelling at the way that Santa always managed to squeeze in useful things like socks and soap.

Fee went to church to ring the Christmas-morning bells. Mena remained behind, bustling between vegetables and sauces, the fridge and the cooker, the freezer, the sherry bottle and the phone. She chased Abren and Bentley away from the presents under the tree, persuading them to wait until after lunch with bribes of chocolate, cakes, biscuits, dates and nuts. All the while she kept nipping at the sherry and by the time that Fee came home, she was singing. Fee said she was drunk, and she said perhaps she was, but that she worked ‘like a skivvy’ all year long and deserved to be excessive once in a while.

It was a day for all of them to be excessive. Mince pies arrived before lunch, washed down with yet more sherry and cheap, fizzy wine. Still more chocolates followed the mince pies, and lunch followed the chocolates in a feast to which there seemed no ending. Soon, half the turkey was a carcass, the Christmas pudding had disappeared, the wine bottle was empty and the trifle was reduced to lumps of jelly floating in a small custard pond. A mountain of dishes sat piled in the sink, ‘to do later’ as Fee put it when Mena looked at him in vain hope.

It was time for presents, he said, not washing-up. They settled round the tree and Fee switched on the fairy lights. Bentley handed round the packages, and books and music tapes, a pair of football boots, a pile of silver jewellery, yet more chocolate, sweaters, games, stockings, perfume, soap and socks started falling out.

Abren opened a book called Homecoming, about a girl called Dicey who’d lost her mother and didn’t have a home. Fee had inscribed the inside cover with the words, ‘I thought you might enjoy this story. Tell me what you think.’ Then Abren opened another package which contained a thick red coat, made on Mena’s sewing machine. Along with it went a woolly hat with flaps, and gloves with furry trims.

Fee had a hat as well, to keep him warm when he went out busking. He also received a huge biography of his all-time favourite cellist, Paul Tortelier.

But Bentley’s was the biggest present of them all.

Fee went downstairs to the ‘music school’ and brought up something encased in blankets because he’d forgotten to buy any wrapping paper. It was a brand-new saxophone, golden and gleaming! Everybody

stared at it in astonishment. Bentley turned bright red.

‘Now you don’t have to borrow mine any more,’ Fee said.

‘But we can’t afford it!’ Mena said.

‘Of course we can – what d’you think I’ve been playing for all this time on Pride Hill?’ Fee said.

He beamed. Point scored. Mena flushed. Abren could see that she wanted to be pleased, but that something was eating away at her.

‘It’s very nice, I’m sure,’ she said, managing a tight smile.

‘Bentley deserves it. He deserves the best. He’s got real talent, and he works hard,’ Fee said.

He beamed at Bentley, full of pride. But Mena flushed as if she’d been stung.

‘Unlike some of us, I suppose!’ she said, ‘who don’t deserve to have hundreds of pounds spent on us, not even for the luxury of a new dish-washing machine!’

For a moment there was silence. Maybe it was the drink that had done it. Fee said something very quiet about spoiling things, and Mena snapped back that the only person being spoiled was Bentley. Bentley clutched his brand-new saxophone, and if it hadn’t been for Abren and her present it wouldn’t have felt like Christmas any more.

Suddenly she saw where she had put it, right at the back of the tree behind everything else. She pulled it out and gave it to Mena.

‘It’s nothing really,’ she said, hoping that it would cheer things up. ‘I just wanted to thank you for everything.’

Mena took the present and looked ashamed, as if she had forgotten all about Christmas, and here it was back again. She opened it up and Abren’s little piece of embroidery fell out. She hadn’t thought to iron it or sew a hem, but it didn’t matter.

‘Oh, Abren!’ Mena said. ‘This is beautiful. Wherever did you get it?’

‘I made it,’ Abren said.

‘You made it?’

Mena stared at the little trees and flowers, the birds and the river, all beautifully stitched. She stared for so long that Abren began to shift awkwardly, wondering if she was going to be told off for stealing the silks and the little bit of cloth. But then Mena leant across and gave her a big hug.

Suddenly it was Christmas again. They sat around the tree, and Mena asked Bentley to play some carols on his new saxophone. It was as if she wanted to show that there were no hard feelings. Fee started reading his Paul Tortelier book, and Mena picked up Abren’s embroidery and came and sat with her.

‘Whoever taught you to sew fairy stitches like these?’ she said. ‘A young girl like you – I can hardly believe it!’

Abren shrugged. She didn’t know.

‘Was it your mother?’ Mena said.

Her mother again. Abren looked away. On the other side of the room Bentley had given up on the carols and was composing tunes of his own. His eyes were closed, and he was playing as if for himself alone. Playing the sweetest notes on his brand-new saxophone, unaware that everybody was listening. Mena sighed as if she’d never known that her Bentley could play like that. Fee beamed with pride. Bentley nursed the saxophone in his arms, coaxing out a tune as if it were a carol composed especially for today.

It rose to the ceiling and rolled across the room. Suddenly Abren recognised what he was playing. It was ‘her’ tune! Her tune again, whispering that she mustn’t worry about her mother and about who had taught her fairy stitches. Whispering that she mustn’t worry about anything. That she was just fine.

Abren listened, mesmerised. She looked at Mena, smiling despite everything. Looked at Fee as he hummed along. Looked at Bentley blowing as if he’d never stop. And suddenly she knew that she had to leave them! She couldn’t keep on like this, playing at happy families. She wasn’t Abren Bytheway. She was another girl. There were things out there beyond the fortress walls of Dogpole Alley that she’d come here to this town to do. Things she’d come to find out. And the tune was calling her to find them. To ask the questions, and to move on.

Abren pulled her little comfort blanket around her shoulders, left the others sitting in the semi-darkness and slipped down into Dogpole Alley. The streets were cold, but the tune had made her strong enough to face them. With it still ringing in her ears, she left the alley and strode across Old St Chad’s Square, passing the iron-grilled gate and following the road round to the Water Lane. She was going to the river, as if she’d always known that it would call her back.

At the bottom of the lane she found the water high and fast after days of rain. The path was flooded right up to the wall, and the river level was high under the railway bridge. But Abren headed towards it without a qualm. Once she’d fought against that dark, old bridge, but she wouldn’t fight again. It was where the river had first brought her – and now it had brought her back again.

Part Three

Dark River

Red

Most nights the town glowed a dull red. It went quiet at six when the workers went home, but was throbbing by ten. You could even hear it under the railway bridge. In between trains rumbling overhead, you could hear the club life around the station. Hear bass lines thumping and drums rattling, and people shouting to each other on their pub crawls round the town. And always they’d end up back here where they’d started, picking up taxis and buying late-night pizzas.

Tonight, however, the streets around the station stood silent and dark. All the clubs were closed, and there was little fun to be had out and about. No neon lights flashed cocktail-lounge signs or offered cheap beer. Even the station lights were out, the platforms standing silent with no trains running and no loudspeakers apologising for anything.

From his hidden world beneath the station, perched up on the girders, Phaze II looked out at the town. It might appear deserted, but he only had to draw back the darkness and there they all would be – the good people of Pengwern with their food and drink and stupid paper hats, their Christmas presents and crackers full of jokes, their tinsel trees and enough cash spent on just this one day to keep him going all year.

But that was scuds for you! Phaze II smiled grimly. Stupid scuds – he hated the lot of them! He pulled his black coat round him, imagining the river rising until it was high enough to fill all their houses, never stopping until they’d been washed away. That’d show them! That’d cut them down to size!

Phaze II would have laughed out loud, but a crowd of boys came along. They entered the tunnel, shouting over the din of the swollen river. Water soaked their trousers and ran over their boots. But it didn’t put them off. It ran against them in waves, but they splashed along the cobbles, breaking bottles and cheering to each other, never looking up to see a boy in the shadows watching everything they did.

Phaze II moved back out of sight, making sure to keep it that way. But he needn’t have bothered. The boys were staggering, plainly drunk. They didn’t know he was there. And neither, for that matter, did they know what danger they were in, larking about on a path whose edge, only inches away from them, lay under water.

But Phaze II knew. He watched their antics and waited for trouble. They were shouting at each other, fighting for the fun of it and chucking more bottles about. Then they fell quiet and Phaze II heard the hissing and rattling of spray cans, and caught a whiff of paint. He moved to get a better view. There were no streetlights underneath him, but it was still possible to make out the BC boys’ special brand of Christmas greeting. It grew across the tunnel wall – a whole new layer of graffiti spelling out in shiny paint just where Jesus, Mary and the town of Pengwern could put their Christmas cheer.

Phaze II knew just how they felt, but it didn’t make him feel any better about them ruining his wall. He willed the boys to hurry up and finish. They had homes to go to, but this was all he’d got. He wanted it to himself, and he didn’t want their ugly graffiti all over it. But as if they had no intention of going anywhere, the boys started yanking the doors off an electricity generator cage, ripping down grills for keeping out pigeons, and scrambling up the niches in the tunnel wall, trying to get up to the girders.

Phaze

II turned away, feeling under threat. Before he could slip away into the darkness, however, a new figure appeared in the tunnel. It came wading along the path with its head down and shoulders hunched, obviously unaware that something nasty waited up ahead. There was nothing that Phaze II could do to warn it – not without giving himself away. He watched the figure approach the centre of the tunnel, where there were no lights and the boys were hanging off the wall. They saw the figure before it saw them – and jumped down in front of it.

Afterwards Phaze II blamed himself. It should have been possible for him to shout a warning without getting caught – a boy like him, who knew the bridge and all its secret getaways! But once the thing had started, there was nothing he could do. The figure looked up, and there they were – a crowd of BC boys bursting for trouble.

‘Well, who do we have here?’

The figure realised that it was in trouble, and tried to back away. But it was already too late. Boys poured out of the shadows, crowding round and blocking off its retreat. Phaze II couldn’t see what was happening, but he could hear them shouting and caught the words witch and bitch and out, out, out. Then the BC boys started pushing the figure about. It tried to break away from them – and suddenly Phaze II got a clear view.

It was the girl, again. The one who’d stared at her reflection in the market door, dressed up in that stolen sweater. The one he would have noticed anywhere, even if he hadn’t dreamt about her, because there was something different about her. And the BC boys didn’t like people who were different. They only liked people just like them. They were frightened of everybody else. Even little girls.

As Phaze II watched, they started laying into her. Obviously they thought that they could get away with it, here under the bridge on Christmas night with the river in full flood and nobody to see. They crowded round the girl, chanting at her and pointing their fingers as if her stumbling into them had made their day.

Mad Dog Moonlight

Mad Dog Moonlight The Red Judge

The Red Judge Midnight Blue

Midnight Blue Sabrina Fludde

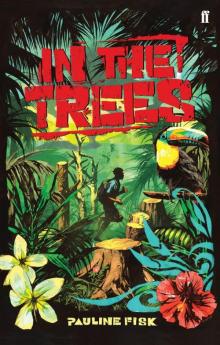

Sabrina Fludde In the Trees

In the Trees